An Ottawa man says in the months since the Montfort Hospital misidentified his brother, allowing strangers to make decisions about his treatment — and ultimately, his remains — their family has endured waves of shock, grief and frustration.

Now they’re getting used to a new feeling — being ignored.

“I think we’re forgotten,” he said. “Everything moved on — no one’s thinking about us, that’s for sure.”

CBC has agreed to identify the man only by his first name, Sam, to protect his privacy, and because not every family member has been informed of all the circumstances surrounding their ordeal.

The family’s last photos of the man who died show him in a hospital bed, covered in tubes and flanked by someone else’s parents.

They were never told when the man was found unresponsive from a suspected overdose on Dec. 30, then placed on life support. It took more than a week after he died before they were even contacted.

By that time, his organs had been donated and his body cremated, all without the people who knew him best having a say in those end-of-life decisions.

There was no chance to say goodbye and no funeral. Instead, another family who believed the man was their son made those arrangements on his behalf.

After the misidentification was discovered, the Montfort shared its condolences and announced a review of what happened. Both the family of the man who died and the family of the man he was mistaken for said they were offered an opportunity to provide input on changes to the hospital’s patient identification policy, but they never heard back.

Now, both families say that lack of communication has only amplified their pain and confusion.

‘I’d like answers’

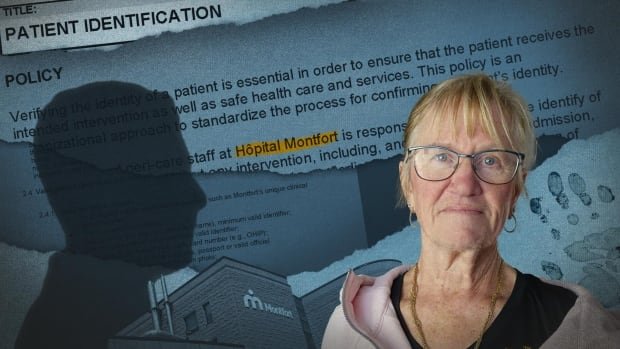

“It just feels like I didn’t matter,” said Heather Insley, the Picton, Ont., mother who spent three agonizing days in January at the bedside of a man she thought was her eldest son, Sean Cox, watching him die.

“I feel very frustrated because this, still, in my mind, isn’t over,” she said. “My son is alive and the other young man isn’t, but I still grieved for that time and … I’d like answers.”

For me, the best apology would be to put things in the system that assures that never happens again.– Sam, brother of deceased patient

Sam, the brother of the man who died, said he’s also waiting to hear from the hospital.

“I feel like we’re owed an apology, an explanation on what went wrong and why it went wrong,” he explained.

He described his brother as smart and witty, the kind of sibling he tried to measure up to, but said a different side of him came out when he was using drugs.

‘Did I do this for nothing?’

Sam told CBC he was encouraged when the Montfort asked him to contribute to the review: Here was a chance to do something to help make sure this tragedy could never be repeated.

He collaborated with friends on a Google document, grappled with medical terminology and spent nearly every spare moment over the course of a month painstakingly crafting suggestions.

They worked right up until the deadline the hospital provided, then submitted their recommendations and asked for feedback.

Sam said the only response he’s received was a request in late July to re-send the document as a different type of file. He hasn’t heard from the hospital since.

The Montfort declined an interview request about its policy changes and its correspondence with the families. The hospital also denied a freedom of information request filed by CBC for a copy of the review.

In a statement sent by email, the hospital’s communications director Martin Sauvé said he was “sorry to hear the families remain dissatisfied” by the hospital’s follow-up, and offered “sincere apologies” for what happened.

He added that the Montfort understands the “frustration that comes with uncertainty,” but pointed to privacy obligations as the reason the hospital has shared only limited information.

Sauvé confirmed both families had the opportunity to provide feedback and said all suggestions were “duly considered and implemented where possible” before the hospital contacted them “in hopes of sharing the new policy.”

Both Insley and Sam have combed through their email and phone logs and said that never happened.

The Montfort shared its updated policy with CBC in August, but as of mid-November Sam and his family still hadn’t seen it. He believes the hospital is obligated to provide them with a copy.

“Did I do this for nothing, or [did] I actually make a difference?” he asked.

Families connected in October

Sam spoke with Heather Insley for the first time at the end of October. During the phone call, Insley tried to help him piece together what happened.

She told him the man was found unresponsive near the Ottawa Mission at the end of December. He never regained consciousness.

A nurse thought she recognized him as Insley’s son, Sean Cox, who had been admitted to the Montfort recently. The nurse suggested staff try to reach his next of kin, according to Insley.

She said a doctor at the Montfort called her on New Year’s Day and told her a family member might be a patient there, then asked for her son’s birth date. When Insley provided it, she was told to get to the hospital as quickly as possible.

They arrived to find a man lying in bed, surrounded by medical equipment and wrapped in a blanket, with tubes covering the lower half of his face. Sean Cox’s name was written on a whiteboard nearby.

Hand prints used to ID man

Insley said her son had been living on the street and she hadn’t seen him in four years. Neither she nor five other family members who visited the hospital ever questioned whether the man in the bed was her son.

Cox has tattoos on both arms and a birth mark on his leg, but Insley said the man’s limbs were concealed by bedsheets, and no one at the hospital asked the family to confirm any identifying features.

It wasn’t until she received a text message from her son — on the same day the man she believed to be Cox was cremated — that Insley began to understand what had occurred.

In the end, Insley said police used hand prints she’d asked the funeral home to take as a memento to reveal the man’s true identity.

After the mistake was exposed, Insley said the hospital told her they’d consider her opinion when weighing changes to its policies, but that never happened.

“I would have appreciated being asked, yes, but I wasn’t asked for my opinion or my input at all,” she said.

‘Beyond any reasonable doubt’

Montfort’s revised policy, translated from French, describes patient identification as an “unequivocal process.”

While the previous document stated physical recognition of a patient by staff could aid in their identification, they’re now required to identify the patient “beyond any reasonable doubt” and must back that up with a second method of identification.

The revised protocol also includes a section about patients who are unable to identify themselves. Those patients face “risks” when it comes to care, according to the policy, which describes “distinctive traits and biometric markers” such as tattoos, birthmarks and scars as part of the process, but not as useful as unique identifiers.

Third parties including police and Ottawa Inner City Health can also help identify patients, according to the policy.

However, “if the identity cannot be confirmed, the patient must remain under ‘unidentified patient’ status until further notice.”

While the previous policy stated it’s “forbidden to presume the identity of a patient who is unconscious,” directing staff to wait for either the patient or someone who knows them to confirm their identity, that detail is missing from the revised document.

‘Decisions were taken for him’

Had she been given a chance to comment on the revised policy, Insley said she would have pushed for fingerprints to be used as the primary identifier of an unconscious patient. Sam said his recommendations stressed harnessing technology to prove a patient’s identity.

The two families, now tied together by a mistake so tragic and unlikely it seems almost unbelievable, share other similarities.

Both believe what happened can’t be swept under the rug. Both know the helpless feeling of losing someone you love to addiction. Both had expected to get a call some day saying their loved one had died.

But neither was prepared for the devastation of misidentification.

Sam described the ordeal as leaving a “wound,” recalling the moment he was told by a police officer.

“As he’s saying what happened, I’m realizing that … there wasn’t going to be any funeral,” Sam said. “[My brother’s] funeral already happened, and some decisions were taken for him that he didn’t want to take.”

Those final photos of Sam’s brother in hospital came from Insley, who said she hopes the images — along with the knowledge that someone who cared was at the man’s bedside — provide them some comfort.

‘One day at a time’

Insley said once she realized her son was still alive, the two briefly reconnected. She visited him at an apartment he’d managed to find in Ottawa, bringing clothes and food.

After the misidentification was discovered, Cox called it a second chance at life, but his mother said they’ve largely lost contact again and she fears he hasn’t changed after all.

In the past year Insley’s husband was killed in an ATV accident and she lost another close friend, leaving her very lonely. A sign hangs on the wall in her living room, offering what’s become her motto for 2024: “One day at a time.”

Insley said she’s started visiting cemeteries in town and cleaning up neglected graves as a form of comfort. Whenever her phone rings with an unknown number, she immediately wonders if someone is calling with bad news about her son — and if this time it will be for real.

She believes the Montfort needs to be held accountable for what happened.

“The other family, their death is final. My son’s wasn’t, but the mental anguish that we suffered … was just as real,” Insley said. “I feel for the other family as their son isn’t coming back and they don’t get a second chance with him.”

Sam said the only apology his family has received from the hospital has come in the form of statements made to and shared by CBC.

They’d appreciate a written message taking responsibility for the harm caused, along with some evidence that his recommendations for the revised patient identification policy were taken seriously, and that change has actually been made at the Montfort, he said.

“If they just continue doing the same thing, it means nothing,” Sam said. “For me, the best apology would be to put things in the system that assures that never happens again.”

Two families united by tragedy when a dying man was misidentified at Ottawa’s Montfort Hospital say they’ve yet to receive a formal apology, nor has the hospital acknowledged their recommendations for improving its policies.